Brazil suffered a major economic crisis in 2014, one whose shock led to a contraction in it’s GDP for 8 consecutive quarters, this article aims to explain a bit about one of the brightest economies of the 2000’s and how severe mismanagement led to one of the worst recessions in the world in recent years and also to link this crisis with IS-LM framework.

The Glory Days

Brazil has always been a country that has been able to set it set self apart in Latin America not only due to its size and its overwhelming stock of natural resources and high value consumer goods (gold, silver, nickel) but also because of its booming economy. The rise of GDP growth in the turn of the millennium and continued sustenance lead many to believe that Brazil was one of the brightest emerging economies in the world, a partnership with the other BRICS nations also helped the spread the image of a growth driven economy. Unlike the other countries that Brazil equated themselves with (India and China which were both driven by growth in the manufacturing sector), they were mostly dependent on exports as a means of growth. The commodities exported by the country include petroleum and other commodity goods, as we can observe all of these goods are highly price sensitive to the international market and as a result their demand fluctuates according to the international price.

The period from 2003 to 2010 was marked by an increasing demand for the commodities that Brazil sold, this increased demand was mainly from Asian countries particularly China, which needed raw materials to keep up with their own growth (real GDP growth was very high during the same period). The president of Brazil at the time Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva enjoyed a surge in popularity and “Aided by the commodities boom, Lula encouraged exports and encouraged the release of credit by public banks to finance development, creating millions of jobs. Diplomatic relations with other developing countries were strengthened and Brazil gained relevance on the international stage.” (Garcia, 2015). It also enabled the left leaning president to oversee a public policy reform (wealth distribution) which lifted around 29 million people out of poverty (World Bank) it also saw a huge rise in the minimum wage across all sectors. The financial crisis of 2008 was also not as bad as expected metrics would have shown and Brazil was able to get away with a fall of only 0.126 % (IMF, report for selected countries and subjects).

Harsh Fall and A Reality Check

Brazils’ days of glory could not have lasted long to begin with, their export driven expansion was a risky idea and the fact that most of their high-volume exports were dependent on international prices also spelled doom. The financial collapse in America which Brazil believed it had avoided would come back to haunt them. In the early 2010’s as demand from China decreased (a slowdown in their GDP growth caused this), and global prices fell the exports went down and the collapse of the economy begin. During this period Brazil elected a new president (supposed spiritual successor of Lula) Dilma Rousseff who continued the socialist policies of the previous government and spent large amounts of money on welfare schemes, while this might have been the correct move politically her government incurred huge deficits because they were unable to finance the schemes. After her re-election in 2014, In the early months of her second term the government owned petroleum company Petrobras was implicated in a corruption scandal, and an independent investigation team later pressed charges against various members of the government, while the people believed that the president was also involved in the corruption scandal. An active distrust in the government and protests over the country asking for her impeachment did little to assure foreign investors as many of them sensed the end of Brazil’s heyday and begin reducing investments in the country.

This was not helped by the fact that the country has a long and complex tax structure which is different from all other countries and the time taken to prepare and pay these taxes was around 2600 hours in contrast the world average was around 254 hours, another aspect that led investors to back out of Brazil was the high wage rates in the country. All of this combined with an inflation rate of 6.5% made prices shoot up and deficits grow.

In addition to this there was also a large growing mountain of debt as the banks had continued to roll out loans to private consumers on the idea that the economic growth would help them repay it back. This could have also been because of Lula’s policies which encouraged banks to lend out. Subsequently the low interest rates and rising middle class who wanted to purchase better goods such as cars and houses made loans more viable and borrowings cheaper. The decision by the banks to keep lending however, is slightly surprising considering the fact that the average income of a Brazilian citizen only increased 0.7% since the 1990’s (World Bank 2019).

Government Policy Actions

The response of the government to the growing economic crisis was bold and shifted focus from socialist welfare programmes towards reducing government debt and decreasing inflation. The policies undertaken by the government were as follows:

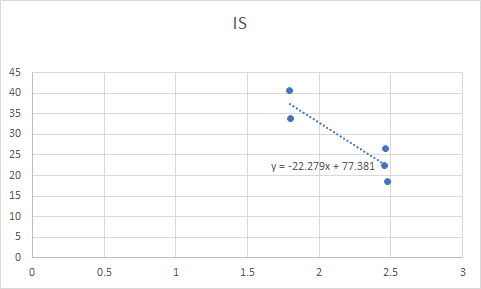

- Fiscal Policy: The major problem the government would have to deal with is that there were large deficits and the surplus the government earned from its public enterprises and exports could no longer be a viable option (also in the short term there was a decrease in revenue from both these ventures. The decrease in private and public spending’s had also caused the IS curve to shift leftwards. The government (mainly new finance minister Joaquim Levy) shifted focus towards reducing the deficits and as a result decided for an austerity measure, a cutback on welfare schemes to decrease deficits

(the above graph shows the IS curve for Brazil during the period 2012-2016, with interest rates on the y-axis and GDP groth rate on the x-axis)

The government policy would have shifted the IS curve towards the left and in an equilibrium state with no monetary policy change would have reduced the equilibrium interest rate and output. This would have helped counteract the high inflation and also increase government surplus (money saved by not spending on the schemes)

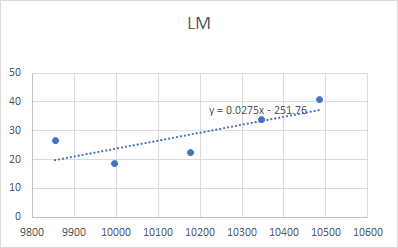

- Monetary policy: The BCB (Banco Central do Brasil ) had a very different policy reaction than one might have expected. Worried by the high inflation numbers almost each quarter since 2014 and finally an explosion in 2015 from 6.3% to 9.03% (IMF) led the bank to increase interest rates.

(the above graph shows the LM curve for the Brazilian economy between 2012 and 2016 with interest rates on the y-axis and real income on the x-axis, the flatness of the LM curve could be due the fact that income inequality is very high in Brazil and majority of the income is held by the rich, for whom changes in interest rate would not be as potent)

The monetary policy would have led to a movement along the LM curve and encouraged people to save more. This policy was very surprising considering its complete contradiction to the policy of the government. It might have also been reactionary and pre-mature as the high inflation in the two years died down to pre-crisis levels in 2017.

Critiques to the policy measures and alternative suggestions

- The first major problem with the fiscal and monetary policy was with the timings, the government failed to predict or prepare for the collapse and as a result had to take instant measures to fix the economy.

- The fiscal policy measures were much needed for the Brazilian state over expenditure on welfare had drained coffers for years but trade surplus had allowed previous governments to get away with this. While the decision to cut back on government expenditure was correct, an economic crisis was not the time to go through with it especially when the people’s faith in the government was already very low. Subsequently people had also grown dependent and to some extent expectant towards welfare schemes so reducing them was not a feasible political strategy, a thought held by the president’s party as she scraped this measure within the next two cycles. It would also imply that changes in government expenditure would have bigger impact on the economy due to the relative steepness of the IS curve.

- The monetary authority for lack of a better phrase must have been over eager to bring down the inflation rate ( that or the savings-interest rate correlation must have really stuck with them), no other reason could explain why the bank would purposefully try to increase interest rate when the government policy was trying to bring it down. The monetary bank must have also forgotten the fact that household debt was very high in 2014 and increasing the interest rate would have a negative impact on the people (increase inflation further as the value of money increased) and would also increase loan defaults.

- An idea that could have been implemented was to move reform measures towards work for benefit schemes such as that followed in India (NREGA). This could have combated two problems, the rising unemployment rate that kept increasing from 2015 onwards and the low levels of infrastructure development, which was 2.1% of GDP (world Bank 2019). While this measure would also require shifting funds from other welfare schemes it surely would have been more acceptable than simply cutting down on them, infrastructure development could also have boosted industries and the government’s willingness to invest would also have provided some reassurance to foreign investors as well as set up a market for manufacturing industries, who could now get access to skilled labour.

Conclusion

After 8 successive quarters of negative growth Brazil finally manged a 1% growth in 2017. While other government policies such as the Labour reform law and outsourcing law were helpful in turning the tides, the major factor causing the reversal has thought to be exports. Exports returned to pre-crisis levels in 2017 as the demand from Asian countries resumed and this helped the economy to bounce back. The IS curve shifted back towards the right due to increased demand and a stable monetary policy helped the economy to a positive growth.

A look back at the affair makes it seem far more surprising and the fact that a demand and price shock (which could have been avoided had the government taken cyclical counter measures) was able to send one of the largest economies in the world to a recessionary state. Paul Krugman described it best in an article in the NYT, “Here’s what it looks like to me: Brazil appears to have been hit by a perfect storm of bad luck and bad policy, with three main aspects. First, the global environment deteriorated sharply, with plunging prices for the commodity exports still crucial to the Brazilian economy. Second, domestic private spending also plunged, maybe because of an excessive build-up of debt. Third, policy, instead of fighting the slump, exacerbated it, with fiscal austerity and monetary tightening even as the economy was headed down.”

The Brazilian economy has made its way out of the storm but the waters ahead are still murky, the effects of the recession still continue as inflation remains relatively high at around 4-5% and unemployment surged to record numbers. A new president has been elected and faith in the government is better than what it was earlier, but work still has to be done to bring the economy back to its glory days.

Very informative and well articulated article. Keep it up!

LikeLike

Excellent article! A very comprehensive analysis.

LikeLike

Very informative and well researched

LikeLike

Really impressive work Rishi

Keep it up!!

LikeLike

Really insightful! The facts are very well presented

LikeLike

Really good work, a lot of interesting information. Keep it up!

LikeLike